By guest author Paul Elvig

There he sat, an elderly gentleman who had recently suffered a slight stroke. He was asking me to set aside the rules so that he could put a small piece of driftwood in a niche with his mother’s ashes. My answer was “no.”

There he sat, an elderly gentleman who had recently suffered a slight stroke. He was asking me to set aside the rules so that he could put a small piece of driftwood in a niche with his mother’s ashes. My answer was “no.”

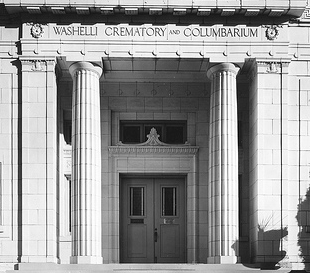

It was 2005 and I was the general manager of Evergreen-Washelli Memorial Park and Funeral Home in Seattle. We had rather stiff rules on what would be allowed in columbarium niches, and we had them for good reason.

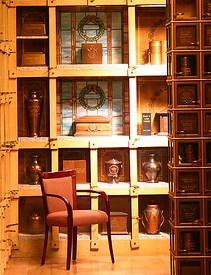

Washelli Columbarium’s point of pride is the quiet dignity it offers visitors: warm rooms, private personal courts, carpeted floors and strict control over niche content.

Washelli Columbarium’s point of pride is the quiet dignity it offers visitors: warm rooms, private personal courts, carpeted floors and strict control over niche content.

In the past we had rejected hand-made airplanes, books that had been authored by the occupant of the niche, photos and nearly any item that did not have “staying power” over a 100-year span. With more than 65,000 niches this can be most important. We had to consider every visitor that would walk through the doors decades from now.

After having his request turned down by another staff member, Mr. K (privacy is respected here) wanted to meet with me about his driftwood.

Mr. K handed me the driftwood and said in quiet tones that he wanted to place it with his mother. I complimented Mr. K on the general beauty of the driftwood, and I told him of our policy regarding wooden objects, which stemmed from our concerns about how long they might last, especially when looking at it from the long-term—perhaps centuries—viewpoint.

He was disappointed, but accepted my ruling. As Mr. K. prepared to leave, I felt a little small talk and some visiting would make him feel better before he left, so I engaged him in conversation.

Mr. K was Japanese-American, born here, yet he had the mannerism of the old country. His courtesy and palpable respect were disarming. We visited about Seattle and the Pacific Northwest and somehow got on to the subject of his youth. I figured him to be about eight years my senior. That meant he likely had been a boy of about seven in 1941.

He was reluctant to go into details at first, but I felt compelled to ask some gently probing questions. Had he been forced to move when World War II broke out? Yes, he had been.

It was during the Roosevelt administration that Japanese-Americans were ordered “for security purposes” to be moved from costal areas, and interned inland. Mr. K’s family was taken quickly, without the opportunity to gather much in the way of personal effects or to say good-bye to neighbors and friends.

His family was taken to an internment camp east of the mountains to join hundreds of other Japanese-Americans also removed without hearing or even so-called due-process. He didn’t understand much about it at the time. He knew his Mother was most worried as he had serious asthma problems.

“I remember Mom pounding on the gate to get the guard’s attention regarding my breathing issues. I remember Mom’s hands bleeding from pounding so hard.” I looked at Mr. K with laser-focused attention.

I was getting embarrassed for my country and thus for myself. I told Mr. K how sorry I was and ashamed we had done such a thing in the name of fear. He held no grudge, which truly amazed me.

“When we got to camp, we didn’t have any toys or anything to play with,” Mr. K said. “The food was okay and we were with family, but it seemed so strange.”

“No toys? What did you play with?” I asked.

“We would pick up most anything and make believe it was a car or a doll,” he said.

As Mr. K started telling me about make-believe I noticed how he reached over to touch the piece of driftwood now sitting on an office chair; driftwood shiny with age and handling.

I was afraid to ask. But I had to.

“Mr. K, what did you play make-believe with?”

His old and tired hands, knotted with arthritis, slowly picked up the driftwood. “This is the car my mother gave me. It’s something I just kept all my life.”

Looking at this wonderful American through my tear-swollen eyes, I said, “We will be breaking the rules, Mr. K. That toy, that piece of hand polished driftwood, that gift from your mother will join her if I have to open the niche myself.”

There is a time to break the rules. There is a time to do what is best for the customer. We must never lose sight of why we are in business in the first place.

Mr. K’s parting handshake was the most wonderful and heartfelt I have ever shared. His was a forgiving hand, mine was a thanking hand.

Mr. K passed away not long ago, but his memory will never pass from my consciousness.

Paul Elvig is the retired general manager of Evergreen-Washelli Memorial Park and Funeral Home in Seattle, Washington. He is also a past president of the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association. He still provides expert testimony on issues relating to the death care industry. To e-mail him, click here.

Paul Elvig is the retired general manager of Evergreen-Washelli Memorial Park and Funeral Home in Seattle, Washington. He is also a past president of the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association. He still provides expert testimony on issues relating to the death care industry. To e-mail him, click here.

Leave a comment